1940-45

He produced works like El Complejo de Edipo (The Oedipal Complex) and Siete hijos y el fantasma de la madre (Six Children and the Ghost Mother) tied to his research in psychoanalysis; El Profeta (The Prophet), El Tibet (Tibet), El Lama (The Lama), and El Mensaje (The Message) tied to Zen philosophy. In works like El Ampurdán (Emporda) and El paraíso perdido y Gaudí (Lost Paradise and Gaudí), he dealt with the landscape of his native Catalonia, and in the series Imagen persistente de un ancestro (Persistent Image of an Ancestor) his own memories.

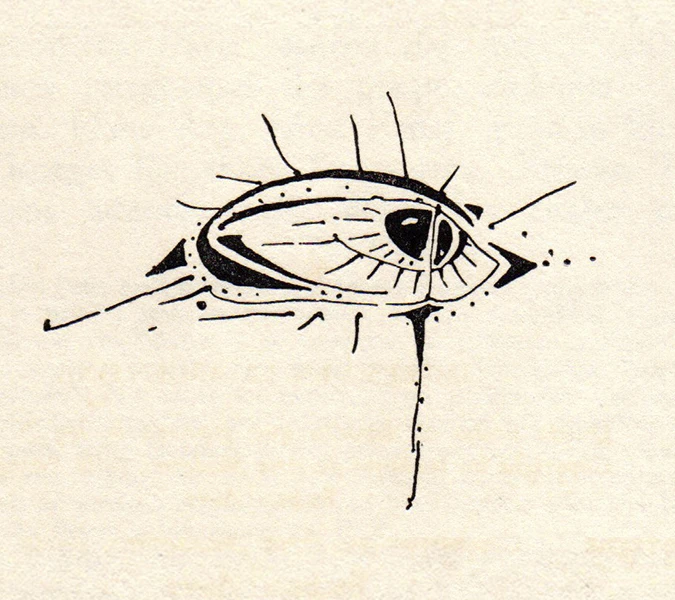

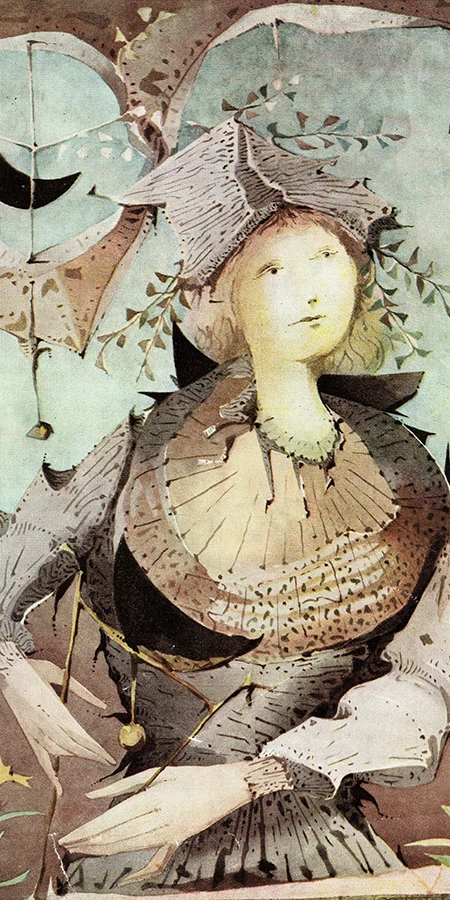

During the same period, he created a new figuration he called Noicas, or—as he described them—"fairies of life and fate."

1945-50

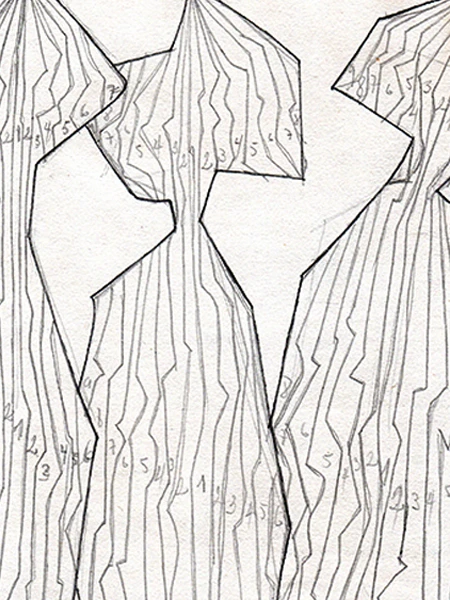

1948. He exhibited the series Los mecanismos del número (The Mechanisms of the Number) that evidences his interest in energetic rhythms, a notion he was key to theorizing.

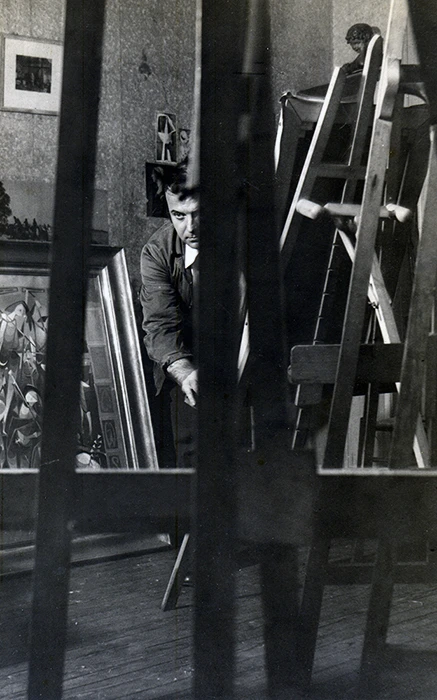

He opened his studio at 938 Santiago del Estero Street in Buenos Aires.

1949. A retrospective of his work was held at the Instituto de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

“

6. Birth from Starting Points, “Fire-Points”.

“The starting points usher in a new overall conception of things. The graphism is enriched with the rhythm and its determination, as well as the connection between those central points and the more distant ones, the images that they yield. They astonished us. That initial pattern resembled the prior construction of a cosmic order in relation to the image about to surface (…) in Fire-Points, surrealist painter Jacques Herold says it with overwhelming poetry: “insofar as crystal is a hereafter of form and matter, painting must be the crystallization of the object, chiefly the human body: a constellation of fire-points from which crystals beam.” Before, he declared, 'One must be clairvoyant, become clairvoyant'.”

”

“Juan Batlle Planas and Automatism” (1947) Introduction by Romualdo Brughetti. Cabalgata magazine Nº 12, Buenos Aires, pp.16-9.

Noica

You have never heard her name.

And yet, when a dream—any dream—braided florescent

nets over the face of time,

Noica was there.

For you, her hair might be the lethargic tide

on which the sky rises up on the first christmas

that hovering bride, her crystal bouquet frosted and a silver ribbon

on her throat, For you, her clothing might be a room where, slowly, leaves fall, diadems of vines and rains When love, its hands of enchanted foliage, knocks.(...)

(1948) Olga Orozco, Poema Noica, Revista Cabalgata N°19, Buenos Aires.

Las Muertes, Editorial Losada, Gulab y Aldabahor, Buenos Aires, 1951, pp.23-24.

“

...Since 1935, we have steadfastly produced our painting using the automatic mechanism. With it, we have identified and come together. We are surrealists and we will persist on that term dogmatically. The orthodoxy of surrealism is what defines us. We hold onto it because fully aware of the work performed by its adherents and because we understand the virtue of automatism. It was not for naught that one day an individual capturing something as if by magic saw how vessels broke in a fountain. But it does not vex us that vessels break in a fountain.”

Juan Batlle Planas (1949), conferencia en el IAM, Instituto de Arte Moderno

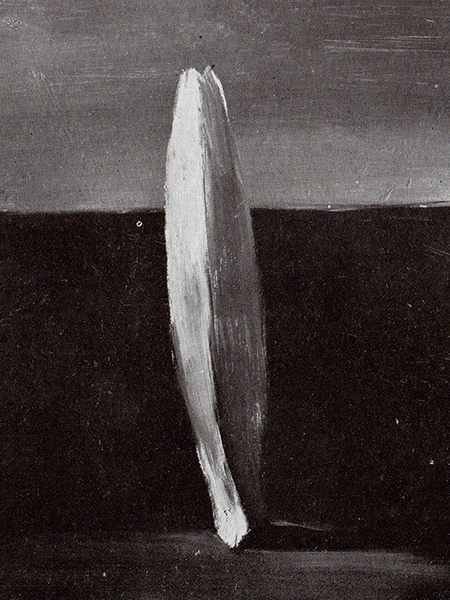

"…And, once again, we find ourselves viewers before Batlle Planas’s paintings, viewers who know that an artist sends a visual message straight to our sensibility, that he takes a non-rational path to make us understand. In his paintings, he speaks to us of angst and vague despair, of reveries, of inchoate aspirations, of ideal entities whose grandeur one could only hope to reach—and all of that in a language of colors never even imagined, of blues and grays so transparent they are only possible in the atmosphere of the dream."

Pellegrini, Aldo (Adolfo Este) (1948) "Juan Batlle Planas’s Visual Message", Cabalgata magazine, Nº 20, Buenos Aires,pp. 1-8-9-16

“… It has been evident since his first works, produced in 1935 (he was clearly in no hurry to show his art), that Batlle Planas turns his back on the real. His decorative projects take the shape of resolutely non-figurative drawings and paintings in two or three dimensions. That art was arguably not yet super-realist; he had not started delving into the unconscious. But we already find ourselves at a distance from intuition and rationalism.”

Payró, Julio (1949) Catalogue to the exhibition, Pinturas y Dibujos 1935-1949, Instituto de Arte Moderno, pp. 5-13.