Juan Batlle Planas

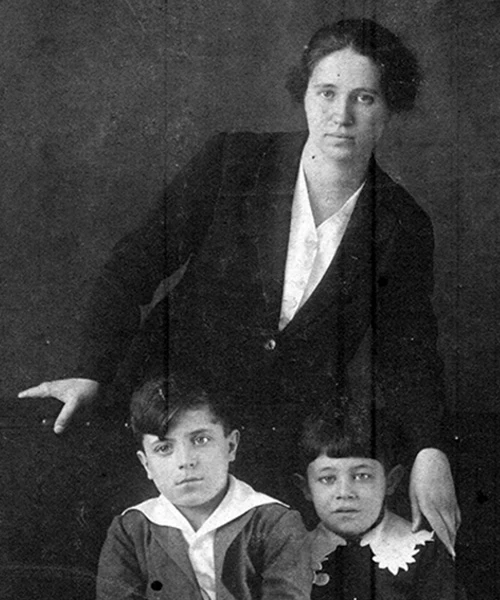

He was born in Torroella de Montgrí, Girona, Spain on March 3, 1911. He and his family immigrated to Buenos Aires in 1913 and moved in with his mother’s relatives when they arrived. His father moved back to Spain, and Juan Miguel never heard from him again. He attended a technical high school.

As a youth, he worked in a engraving workshop with his uncle, José Planas Casas, and Pompeyo Audivert. During these years, he came into contact with Zen philosophy through a teacher whose identity the artist would never reveal, though he had a profound influence on his life and work.

A clear exponent of the twentieth-century avant-gardes, Juan Miguel was a self-taught artist. Because of his researcher’s spirit, he was constantly pursuing new knowledge. His work encompassed contemporary thought on science, mathematics, art, surrealism and its automatic processes, and psychoanalysis through the theories of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Wilhelm Reich, and Gestalt.

Nearly one hundred individual exhibitions of his work have been held and his art has been featured in over five hundred collective exhibitions at prestigious galleries in Buenos Aires and throughout Argentina, as well as abroad. He produced twenty-seven murals.

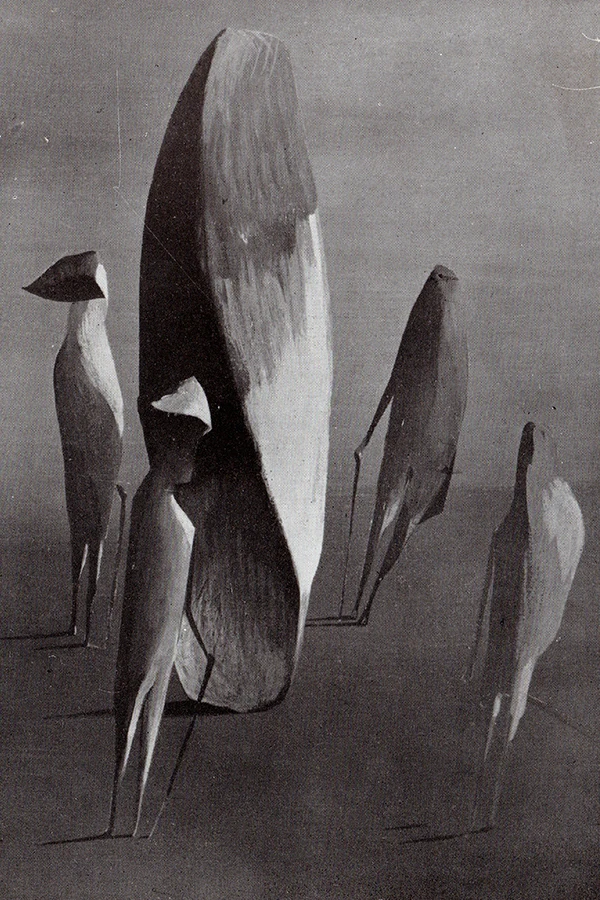

He experimented with different techniques and media, producing zincographs and linocuts, drawings in ink and pastel, collages, paintings in tempera and oil, objects—many of them mixed media boxes—works in painted glass, tapestries, jewelry, murals, sketchbooks, and poems.

He founded the Private Institute for Research on Form.

He devised creation systems based on energetic mechanics.

He gave seminars on the psychology of form, modern art, and painting technique, and courses on surrealism, surrealism and psychoanalysis, aesthetics, and the psychology of art.

He published a number of articles on art theory and the psychology of form.

He was awarded the Palanza Prize, a greatest honor given by the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes.

He was an honorary member of the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes.

He was the mentor of outstanding artists like Roberto Aizemberg, Julio Silva, Noé Nojechowicz, Jorge Kleiman, Juan Andralis, among others.

A maverick in a milieu where realism and academic painting prevailed, he had an impressive ability to create images.

He died in Buenos Aires on October 8, 1966, at the age of fifty-five.

“

Hieronymus Bosch and Comte de Lautréamont—they were the ones who guided, who instructed, my painting’s exploration, as did Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death, as did Halley’s Comet, as did Emeric Essex Vidal’s paintings, as did the four corners that shaped the intersection of Matheu Street and what was Victoria Street (The English Graveyard, now 1 de Mayo Plaza), as did that other painting—the one that shows a boy staring out at his fate while in a dark blue background dwells a sky that lights up the castle of Torroella de Montgri (the place of my birth).

”

Juan Batlle Planas manuscript.

...I don’t sail in calm waters, nor do I have the winds at my back. Only released do I hold that the possibility for creation is generated by the workings of an inner mechanics. Painting, sculpture, poetry, etc., means, through its technique, slackening or reparation. That inner mechanics is furthered by the bequest of nature, a bequest that, because expelled, carries on.

Juan Batlle Planas Revista (1961) Intervview of Oscar Mara, Revista Hoy, N°1, Buenos Aires.

“

Batlle was the one who, in his day, most intensely stirred up the surrealist spirit. Though I have never been tied down by any orthodoxy, I have always loved how much surrealism can free the spirit and incite all the powers of the imagination. Batlle’s painting showed me our surrealist attitude in an unprecedented,...

”

Molina, Enrique (1975) Crisis magazine Nº29.

“

To remember Batlle is, for me, to hold up to the light situations rich in wisdom and affection, the teachings of a true mentor who saw me through and stirred me up….

There is no way I could sum up Batlle’s teachings, but I do feel the need to recall—perhaps at random—some of the things I heard him say, reflections full of wisdom and, as such, a constant call to transformation and to see more and more clearly our own work:

“The decorative in painting is usually a sign of the human.”

”

Nojechowiz, Noé “The Call to Transformation,” Crisis magazine Nº29, September 1975, p.73.

“

…More than a memory, I am left today with his steadfast presence. And I can feel his endless human sympathy, his smile, hands, eyes, a precise and extremely delicate clarity—as well as his severe arbitrariness at times. He could reach the heights of insight, but also sink into the depths of irrational spite—perhaps because he was such a lonesome man.

”

Aizemberg, Roberto (1975) “The Two Storms”, Crisis magazine Nº29 29, p. 71-72.

“All those who were Batlle Planas's disciples coincide in pointing out the magnetism emanating from his personality. For those who were not so close to him, the circumstancial man, of strong appearance with the penetrating and distant light-blue gaze, sparse and sibylline in his language gives us a glimpse of a fascinating world, only to be grasped through his painting or his poetry. The early task of spiritual search he undertook trying to find a point of confluence between the scientific and the artistic was not only a phase but the constant trait that he would uphold all along his life...”

Whitelow, Guillermo (1981) “Obras de Juan Batlle Planas”, Exhibition catalogue of Banco Mercantil Fundation, Ruth Benzacar Editions.